Press Release

|

Considering History: Juneteenth, Rosa Parks, and Finding Inspiration in Our Hardest Histories. June 20, 2022 For this year’s Juneteenth commemorations, a new documentary and a just-published book on the life and legacy of Rosa Parks together exemplify that goal of finding inspiration in our most painful histories.

Weekly NewsletterThe best of The Saturday Evening Post in your inbox!This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present. This year’s commemoration of Juneteenth marks the first time that the anniversary of emancipation will be celebrated as a federal holiday, but only 18 states currently recognize it as such. There are a number of factors that have contributed to the mixed reception to the newest federal holiday, including to be sure the overt public racism which has been such a defining feature of the last decade of American life. But also playing a role is the idea that hard histories like those of slavery and racism are largely a source of negative emotions like guilt; people fear that these negative emotions will only add divisiveness and pain to our society. Grappling with the worst of American history is certainly not easy, not in classrooms and not in collective commemorations. But I’ve long argued that it is only through such engagement with our grimmest histories that we can be inspired by the best of us, by models of our national ideals in action. For this year’s Juneteenth commemorations, a new documentary and a just-published book on the life and legacy of Rosa Parks together exemplify that goal of finding inspiration in our most painful histories. The documentary, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Parks, premiered this past weekend at the Tribeca Film Festival and is available for digital purchase. Working from Jeanne Theoharis’s 2013 book of the same title, directors Yoruba Richen and Johanna Hamilton pull together footage of Parks, stories from her family and peers, and interviews with scholars and activists to tell the complete story of Parks’s lifelong fight for civil rights. In their conversation with the Women & Hollywood project Richen and Hamilton note that Parks herself recognized how “interviewers tended to only ask her about the one incident on the bus in 1955 and nothing else. She got pigeonholed and stuck in time in the public consciousness.” In pushing back on that pigeonholing and instead exploring the entirety of Parks’s life, the documentary also forces audiences to engage much more fully with the vital role that Parks’s childhood experiences of racism and white supremacist violence played in forming her perspective. Parks was repeatedly bullied by white children in her Montgomery neighborhood, she has a vivid memory of her grandfather guarding their home with a shotgun as the Ku Klux Klan marched down the street, and her school, the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, was burned twice by arsonists. These childhood traumas are not only an inescapable part of Parks’s story, but they also help us understand her inspiring, lifelong response to such treatment. As she put it, “As far back as I remember, I could never think in terms of accepting physical abuse without some form of retaliation.” Unfortunately, at no point in Parks’s life was she able to entirely escape such abuse. H.H. Leonards’s newly released book, Rosa Parks Beyond the Bus: Life, Lessons, and Leadership (2022), takes as its starting point one of the final traumas that Parks underwent and transcended. In 1994, an 81 year-old Parks was assaulted and robbed in her Detroit home; she was badly injured in the attack but even more psychologically affected, and did not feel safe returning to her home after the incident. Willis Edwards, an NAACP leader and friend of Parks’, learned of the heroes-in-residence program at Leonards’ Washington, DC O Museum in the Mansion, a program that would allow Parks to stay for free (she struggled financially for most of her final decades) and in complete privacy while she recovered. She ended up living with Leonards for nearly and decade and the two women became quite close, an experience about which Leonards writes at length in her book (having never talked about it publicly while Parks was alive).

I had the chance to interview Leonards about her book for this column, and she emphasized in particular the ways Parks responded to and transcended such traumas. As Leonards puts it, “She was a survivor and the ultimate ‘influencer’ of generations to come,” attributes embodied by Parks’s response to this late-life attack and its aftermaths. Speaking about Parks’s perspective and work during her decade after the attack, Leonards adds, “I want people to know that although she had a very difficult life, no matter what happened to her, she always managed to take time to heal physically and emotionally and then would roar back, stronger than ever.” Exemplifying that inspiring response is the way Parks doubled down on her support for Black youth, rather than giving in to media narratives of her 1994 attacker, a troubled and drug-addicted young Black man named Joseph Skipper, as an illustration of a lost generation.

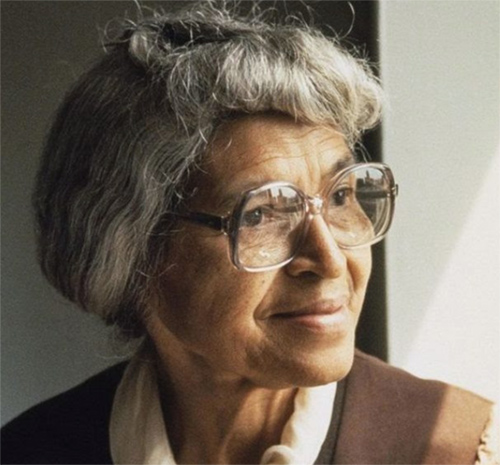

Leonards’s book and perspective also help put Parks’s role in the bus boycott in a different and even more inspiring light. As I wrote in one of my first Considering History columns, that boycott arose out of activism by Parks and many others on behalf of Montgomery’s Black women, women who had, as Leonards puts it, “suffered rape and other untold indignities. These are women who endured discrimination in employment, age, and gender. They managed to survive, and made a way when there was none.” Parks was one of those women in every sense, but she was also a spokesperson and leader in the fight to gain rights, justice, and equality for them. Leonards links that leadership role — that ability to turn some of the hardest histories into inspiring collective activism — to Parks’s lifelong profession as a seamstress, arguing that “in the bigger picture, she sewed pieces of people’s lives together throughout the world and lifted them up with tenacity, hope, and pure love.” Continuing to lift up those lives and stories, extending Rosa Parks’s life and legacy here in our profoundly fraught and traumatized 21st century moment, remains a vital collective task. Leonards chose to publish her book with R.H. Boyd Publishing, America’s oldest Black-owned publisher, who are themselves and example of an inspiring voice in that longstanding and ongoing effort to amplify these important stories. As Leonards describes it, “The company was founded by formerly enslaved Reverend Richard Henry Boyd, who did not learn to read and write until he was 29. The founder was a kindred spirit to Mrs. Parks. R.H. Boyd’s great-great granddaughter, Dr. LaDonna Boyd, now runs this 125-year-old publishing company. Dr. Boyd’s vision, mission, and values are in keeping with what Mrs. Parks taught.” Featured image: Rosa Parks (Wikimedia Commons)

|